By Jamey Cross

Nash Consing and Brianna Gilbert try not to let the 2,506 miles separating where they live come between them. Despite the physical distance, the two college sophomores have grown closer with the help of hours-long FaceTime calls and nonstop texting.

“I love yous” written on gum wrappers and Post-its adorn the walls of the two college students battling time and space in their long-distance relationship.

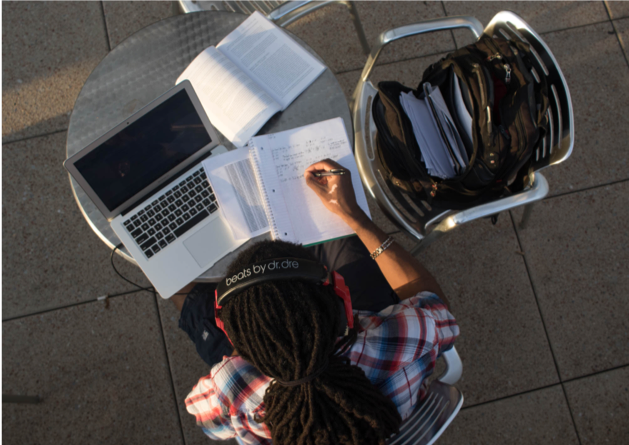

Consing, a photojournalism and communications student at UNC-Chapel Hill, never saw himself in a long-distance relationship. Gilbert, a biology student at California State University in Fullerton, didn’t either. But that was before they found a relationship that made the inconveniences of long-distance romance worth it.

In January, Consing boarded a California-bound plane to meet a girl he’d fallen in love with over the internet.

Finding each other

In 2014, Consing started posting his poetry on Instagram. By 2015, the account had more than 11,700 followers. Gilbert frequented her Instagram’s ‘Discover’ page, looking for inspiration and motivation. She found both in Consing’s poetry.

“He wrote poetry in a way that kind of spoke my thoughts in a way I could never articulate,” she said.

Gilbert followed his journey as a poet, messaging him randomly over the years. When he announced that he would stop updating the page in January of 2018, she reached out to thank him for sharing his work for so long.

As the two returned to college for the spring semester, they casually kept in touch and grew to be close friends. They’d tag each other in dog-related memes on Instagram, Gilbert said, solidifying their relationship as “friendly acquaintances.”

In May, they had their first FaceTime call, which lasted for 20 awkward minutes. Their second, the two took turns sharing details of their lives for over five hours.

Consing had friendships grow as a result of his poetry account before, but felt something more with Gilbert.

“With her it was different,” he said. “I had this gut feeling.”

For the rest of the summer, they talked constantly. Without distractions, they talked for hours and learned more about one another every day. While the distance was a barrier, Consing said it did help them build a strong foundation for their relationship through honesty and openness. They had no reason to be anyone but themselves, because they had nothing to prove.

When Gilbert realized she was having serious feelings for a guy who only existed to her through her cell phone screen, she was terrified. She had developed a close connection to Consing over the phone, so she knew she wanted to give it a chance.

With school starting back in the fall and all the distractions that come with a new semester, they knew it would be a difficult transition for their budding relationship. But, Consing said, there was no hesitation.

“It was a question of how are we going to make this work, not if we were going to make it work,” he said.

Gilbert fondly remembers the days when Consing’s former roommate referred to her as “Nash’s robot girlfriend.”

Up until that point, around August, they’d been taking their relationship one day at a time. Not putting too much hope into the idea that it would work out.

Still, they decided they wanted more of a commitment. They dropped the “robot,” but Gilbert said Consing didn’t feel like her boyfriend. That word was too weak for what he meant to her.

“He’s my person, that’s what I tell people,” she said. “He’s everything.”

New year, new state

In August, Consing decided to bite the bullet and buy a plane ticket to California. They’d been talking about trying to meet one another, but no concrete plans had been made.

Consing said he remembered her getting home and just breaking down. She’d had a rough day. Her mom had been in a bad mood and work had been tough, so she confided in Consing, and he surprised her with the news.

She kept crying, but now they were hopeful tears instead of woeful ones. It was real.

The countdown began: his flight was Jan. 1, 2019. He booked the flight nearly four months early, with no hesitation or doubts in his mind.

“Every day was a celebration, because we were one day closer to meeting,” he said.

Overall, the days went by quickly, until around mid-December when Consing got home for the winter break. With no distractions, the anticipation nearly drove him crazy.

As Gilbert’s final exams wrapped up, Christmas traditions with her large family started, so the nervous excitement didn’t hit her until the day of the flight.

She remembers pacing around her apartment, envying the calmness of her friends there with her. He remembers lugging his suitcase and camera equipment through airport after airport with sweaty hands.

He called her when he landed. She was already waiting by the terminal four exit at Los Angeles International Airport. Every time she saw a person in yellow, her heart would drop to her stomach. The second he saw her, his chest felt tight and his vision was shuttered.

She watched, unable to control her wide smile, as he made his way to her. He wrapped his arms around her, finally holding his love in his arms.

“It was surreal,” they said.

They hadn’t given much thought to the rest of his week-long trip, as most of their thoughts and anxiety had been focused on the moment in the airport. The busy parts of their week together were spent traveling across California, hiking in Yosemite and spending time with Gilbert’s family.

Toward the end of the week, they got to slow down. They brushed their teeth and ate breakfast together—coffee, toast and peanut butter. Consing got to experience the compassionate, driven and open person he’d gotten to know online.

“Nothing’s perfect, but that trip was perfect,” Gilbert said

With the intense joy they felt finally getting to be together, there was also a sadness in knowing he would have to leave soon. However, the recognition that he would be gone soon made them enjoy the small moments together even more. Gilbert said she made a point to remain present and experience their togetherness while she could.

“I just didn’t want to leave her,” Consing said. “It was never going to be enough time.”

In a crowded LAX, they were forced to say their goodbyes.

Making it work

Edie Campbell is a licensed marriage and family therapist practicing in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. Campbell primarily works with couples, helping them grow as individuals and ultimately strengthen their relationships with one another.

Campbell said in any relationship, communication is key. While physical intimacy and togetherness is not the most important thing in a relationship, togetherness does allow connection that can be hard to replicate over the phone.

“Relationships are difficult enough in the best of situations, so in a long distance relationship especially, you have to be 100 percent invested,” Campbell said.

According to a 2012 article in the American Psychological Association’s Journal of Counseling Psychology, as many as 75 percent of American students report having a long distance relationship at some point during college. In addition, at any given time, 35 percent of college students are in a long distance relationship.

“I never thought long distance was for me,” Gilbert said. “I guess I just had to find someone who made it worth it.”

Gilbert and Consing are making plans for her to visit North Carolina in May. Bojangles and barbeque are at the top of the agenda.

Consing said he and Gilbert are investing in their relationship. They’re working hard every day to make it work. He knows communication is healthy for all relationships, but says it’s crucial for a long-distance relationship.

Until May, Consing will feel close to Gilbert while he has his breakfast—coffee, toast and peanut butter. Postcards and letters she’s sent him adorn the walls of his dorm room. The plane ticket hangs over his desk. A white United States Postal Service box with “Brianna” scribbled across one side sits on his shelf holding other notes and trinkets she’s sent him.

“When you do long distance, I think it has to be all or nothing,” Consing said. And he is all in.

Edited by Spencer Carney.