By Jessica Abel

Sixteen years ago under the florescent lights of University Family Physicians in Charlotte, a little girl with dark blond ringlets rode her plastic tricycle around her mother’s office.

She waved at the nurses who gave her brightly colored lollipops as she passed the front desk. She smiled at the patients who were always glad to see her speed down the halls on her signature blue and yellow three-wheeler.

From age 4, she saw people in pain and sickness being loved by a community. From age 4, Jane Henriques was destined to be a doctor just like her mom.

Now a 20-year-old pre-med student at UNC-Chapel Hill, Henriques is following her destiny. She’s a biology and anthropology double major. She cares for sick children as a volunteer at UNC Hospitals. She’s a licensed EMT, chair of Carolina for the Kids charitable organization and frequents health care lectures through the UNC-CH club, The Medical Dialogue.

There are only four letters standing in her way.

MCAT.

The MCAT, or Medical College Admissions Test, is the standardized exam required by all medical schools. Broken down into four sections that cover the breadth of a pre-med education, the MCAT tests students’ knowledge and reasoning as well as their test-taking stamina. A perfect score of 528 is nearly unheard of.

“The MCAT is the barrier to becoming a doctor,” John Robertson, an instructor and tutor at the Princeton Review, said.

Robertson spoke on Jan. 24 at UNC-CH’s MCAT Info Session, a free event coordinated by the Learning Center and The Princeton Review. It was over an hour long, devoid of free food and filled with sobering medical school admissions statistics.

The room was at capacity 20 minutes before the session began.

Breaking it down

“The MCAT takes complex human beings and squishes them down into numbers you can compare on an Excel sheet,” Robertson said to the standing-room-only crowd. “They’re trying to write the questions so that you get them wrong.”

Henriques is well aware of the MCAT’s deception methods, but takes them as a personal challenge to succeed.

“They will purposefully take an article, switch the order of the paragraphs and add in a thesis that isn’t even related,” she said, thinking about the Critical Analysis and Reasoning Skills, or CARS, section. “They are absolutely trying to trick you.”

CARS is recognized as the toughest section on the exam because it tests reasoning and focus instead of formulas and facts. Science and math-geared students often struggle.

But not Henriques.

Science meets fiction

Henriques credits a childhood filled with fiction as her secret weapon.

In elementary school, she relished the American Girl books, historical fiction stories about young women pursuing seemingly impossible dreams. She tore into intense series like Artemis Fowl and Harry Potter, navigating the tangled storylines with ease. Oh, and there was that intense vampire stage after “Twilight” was released. She laughs about it before tossing her still blond ringlets behind her shoulder.

These stories set the groundwork for Henriques’ understanding of nuance in narratives. Today, she uses those skills to decode CARS passages like a recent essay on the historical and symbolic significance of bears in North America.

“It’s not what you’d expect to find in the MCAT,” Henriques said, “but, personally, I find the passages really interesting. I think it’s what helps me do well.”

Opportunity costs

The exam’s masterful manipulation also drove Henriques and her 17 Princeton Review classmates to enroll in an MCAT review class despite the $3,000 price tag. That cost is on top of the $315 initial registration fee, travel expenses and anywhere from $100 to $500 for study materials.

But undergoing financial strain is just one of ways she has sacrificed for the exam.

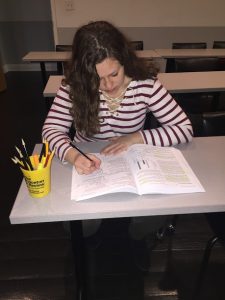

Every Saturday morning while her neighbors in Townhouse Apartments are recovering from Friday night in a college town, Henriques prepares for three hours of grueling review. Her king-sized bed has become semi-permanent storage for over 40 pounds worth of biology textbooks, test prep guides and study sheets.

Every Saturday morning while her neighbors in Townhouse Apartments are recovering from Friday night in a college town, Henriques prepares for three hours of grueling review. Her king-sized bed has become semi-permanent storage for over 40 pounds worth of biology textbooks, test prep guides and study sheets.

She rolls out of bed, throws on a sweatshirt and grabs some yogurt and granola from the fridge she shares with her roommates, Leah and Whitney. Then it’s a hilly, mile-long trek up Hillsborough Street to the office.

She does this four times a week.

The class’s intense schedule has left Henriques feeling a little alone at times. She hasn’t spent a weekend at home all semester.

“I get really homesick,” she said. “I love my family so much. My mom said I can come back any weekend I want, that she’ll just pick me up so I can do laundry and hang out. But I can’t. Not when I have class Saturday and Sunday.”

But for Henriques’s family, this level of commitment is nothing new. It’s just a sacrifice they’ve all made for her dream.

“There was never a time she didn’t want to be a doctor,” Dr. Anna Guyton, Henriques’ mother, said. “Never even an astronaut or ballerina phase. For whatever reason, it was always ‘I want to be a doctor.’”

Students who study without an official review course like Henriques’ Princeton Review class save $3,000, but often feel the same amount of academic pressure as students taking a course.

“It can feel like you’re stuck flipping through the same book over and over and over in search of the myths of organic chemistry,” joked Sean Adkins, an academic coach at UNC-CH’s Learning Center.

Anusha Doshi, a junior biology and chemistry double major with a French minor on the pre-med track, decided to save the money and brave the organic chemistry book, as well as a dozen others, on her own.

She completes one chapter — 30 pages of reading — each day and uses the weekends to catch up. She’s timed it so that her summer can be used for practice tests and final review. Sometimes she and her friend, Amanda, study together just to remember that someone else is going through it, too.

Hard work pays off

Like Henriques, Doshi works each day with the goal of joining a community dedicated to helping others. The stress, time and effort can be overwhelming, but, once in a while, there are moments that remind her it’s all worth it.

Last fall, she was dressed in her Carolina blue volunteer polo shirt in the art therapy room at UNC Hospitals.

She walked up to an elderly man and offered to make art with him. She learned he had stage IV colon cancer. It was terminal. His family hadn’t visited in months.

She gave him her time, her patience, an afternoon filled with conversation and creation. He turned to her to thank her when she had to leave.

“He said, ‘I am so glad you came here and sat with me. Today, you made a dying man smile,’” she said.

Edited by MaryRachel Bulkeley